At 10 p.m. on the 23rd Beijing time, Fed Chairman Powell made a major statement at the Jackson Hole Global Central Bank Annual Meeting. During the meeting, Powell sent the clearest signal so far of a rate cut, stating that the time for policy adjustment has come. The timing and pace of interest rate cuts will depend on subsequent data, changes in outlook, and risk balance.

At 10 p.m. Beijing time on the 23rd, Federal Reserve Chairman Powell made a significant statement at the Jackson Hole Global Central Bank Annual Meeting.

During the meeting, Powell delivered the clearest signal of a rate cut so far, stating: The time for policy adjustment has come. The timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on subsequent data, changes in outlook, and risk balance.

He believes that the current policy rate level provides the Federal Reserve with ample room to address any potential risks, including the risk of further deterioration in the labor market situation. 'The upside risks to inflation have weakened, while the downside risks to employment have increased. The Federal Reserve is paying attention to the risks facing each of its dual mandates.'

He believes that the current policy rate level provides the Federal Reserve with ample room to address any potential risks, including the risk of further deterioration in the labor market situation. 'The upside risks to inflation have weakened, while the downside risks to employment have increased. The Federal Reserve is paying attention to the risks facing each of its dual mandates.'

The full text of the speech is as follows (in Chinese and English comparison):

Four and a half years after the arrival of the COVID-19, the most severe economic distortions related to the epidemic are fading. Inflation has significantly declined. The labor market is no longer overheated, and the current conditions are not as tight as before the epidemic. Supply constraints have normalized. The risk balance of our two mandates has changed. Our goal has been to restore price stability while maintaining a strong labor market, avoiding the sharp rise in unemployment that was typical of earlier disinflationary episodes when inflation expectations were not well anchored. We have made significant progress toward this goal, although the task is not yet complete.

Four and a half years after the arrival of the COVID-19 virus, the most severe economic distortions related to the epidemic are dissipating. Inflation has significantly decreased. The labor market is no longer overheated, and the current situation is not as tight as before the epidemic. Supply limitations have normalized. The risk balance of our two missions has changed. Our goal is to restore price stability while maintaining a robust labor market and avoiding a sharp increase in the unemployment rate, which typically occurs in early disinflation episodes when inflation expectations are not well anchored. We have made significant progress toward this goal. Although the mission is not yet complete, we have made significant strides towards this outcome.

Today, I will start by discussing the current economic situation and the future path of monetary policy. I will then delve into the economic developments since the onset of the pandemic, exploring why inflation soared to levels not seen in a generation and why it has dropped significantly while unemployment has remained low.

Today, I will first discuss the current economic situation and the future path of monetary policy. Then, I will turn to a discussion of economic events since the pandemic, exploring why inflation has risen to its highest level in a generation and why the inflation rate has fallen so much while the unemployment rate remains low.

Near-Term Outlook for Policy

Let's begin with the current situation and the near-term outlook for policy.

Let's begin with the current situation and the near-term outlook for policy.

For much of the past three years, inflation ran well above our 2 percent goal, and labor market conditions were extremely tight. The Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) primary focus has been on bringing down inflation, and appropriately so. Prior to this episode, most Americans alive today had not experienced the pain of high inflation for a sustained period. Inflation brought substantial hardship, especially for those least able to meet the higher costs of essentials like food, housing, and transportation. High inflation triggered stress and a sense of unfairness that linger today.

For much of the past three years, inflation ran well above our 2 percent goal, and labor market conditions were extremely tight. The Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) primary focus has been on bringing down inflation, and appropriately so. Prior to this episode, most Americans alive today had not experienced the pain of high inflation for a sustained period. Inflation brought substantial hardship, especially for those least able to meet the higher costs of essentials like food, housing, and transportation. High inflation triggered stress and a sense of unfairness that linger today.

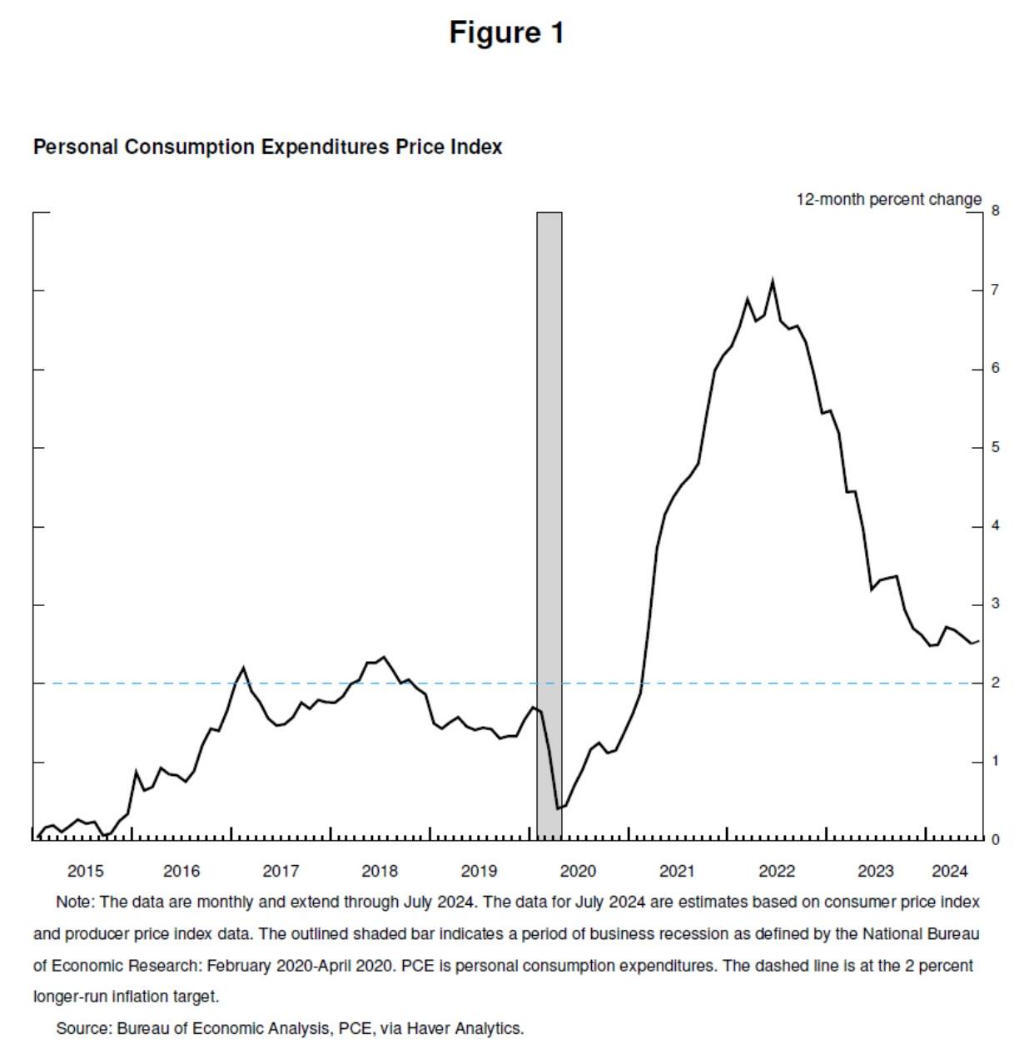

Our restrictive monetary policy helped restore balance between aggregate supply and demand, easing inflationary pressures and ensuring that inflation expectations remained well anchored. Inflation is now much closer to our objective, with prices having risen 2.5 percent over the past 12 months (figure 1). After a pause earlier this year, progress toward our 2 percent objective has resumed. My confidence has grown that inflation is on a sustainable path back to 2 percent.

Our restrictive monetary policy helped restore balance between aggregate supply and demand, easing inflationary pressures and ensuring that inflation expectations remained well anchored. Inflation is now much closer to our objective, with prices having risen 2.5 percent over the past 12 months (figure 1). After a pause earlier this year, progress toward our 2 percent objective has resumed. My confidence has grown that inflation is on a sustainable path back to 2 percent.

Turning to employment, in the years just prior to the pandemic, we saw the significant benefits to society that can come from a long period of strong labor market conditions: low unemployment, high participation, historically low racial employment gaps, and, with inflation low and stable, healthy real wage gains that were increasingly concentrated among those with lower incomes.

Talking about employment, in the years before the outbreak of the pandemic, we saw the significant benefits that strong long-term labor market conditions brought to society: low unemployment rate, high participation rate, historically low racial employment gap, and stable low inflation, healthy and increasingly concentrated real wage growth among low-income groups.

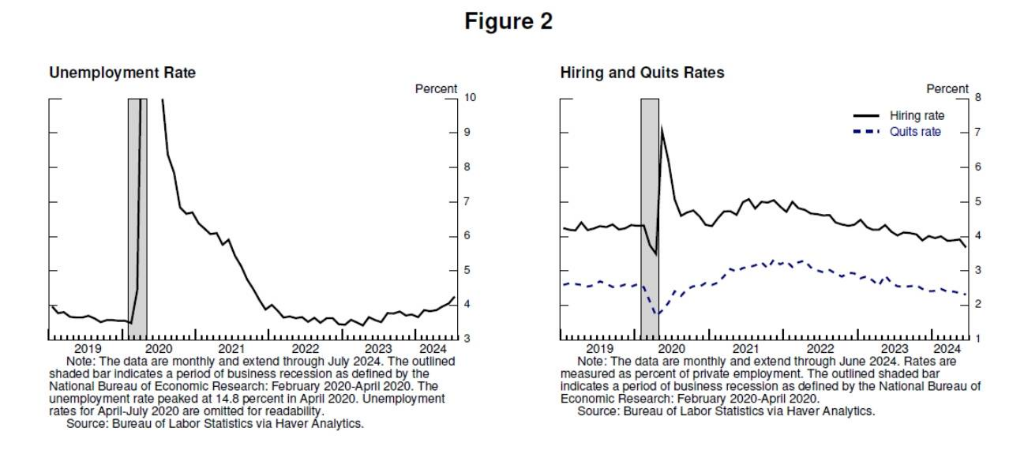

Today, the labor market has significantly cooled from its previous overheated state. The unemployment rate began to rise over a year ago and is now at 4.3 percent—still low by historical standards, but almost a full percentage point above its level in early 2023 (figure 2). Most of that increase has occurred in the last six months. So far, the rise in unemployment has not been due to increased layoffs, as is typical in an economic downturn. Instead, the increase primarily reflects a substantial rise in the supply of workers and a slowdown from the previously rapid pace of hiring.

Now, the labor market has cooled significantly from its previous overheated state. The unemployment rate started to rise over a year ago, currently standing at 4.3%, still relatively low by historical standards, but almost a full percentage point higher than early 2023 (Figure 2). Most of this increase has occurred in the past six months. Thus far, the rise in unemployment is not a result of increased layoffs, which is typical during an economic downturn. Instead, this increase mainly reflects a substantial increase in labor supply and a slowdown from the previously rapid pace of recruitment.

Overall, the economy continues to grow at a solid pace. But the inflation and labor market data show an evolving situation. The upside risks to inflation have diminished. And the downside risks to employment have increased. As we highlighted in our last FOMC statement, we are attentive to the risks to both sides of our dual mandate.

In general, the economy continues to grow at a stable pace. However, the inflation and labor market data indicate that the situation is constantly changing. The upward risks to inflation have weakened, while the downward risks to employment have increased. As we emphasized in our previous FOMC statement, we are focused on the risks associated with both aspects of our dual mandate.

The time has come for policy adjustment. The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

Now is the time for policy adjustment. The direction of progress is clear, and the timing and pace of interest rate cuts will depend on upcoming data, the changing outlook, and the balance of risks..

We will do everything we can to support a strong labor market as we make further progress toward price stability. With an appropriate dialing back of policy restraint, there is good reason to think that the economy will get back to 2 percent inflation while maintaining a strong labor market. The current level of our policy rate gives us ample room to respond to any risks we may face, including the risk of unwelcome further weakening in labor market conditions.

We will do everything we can to support a strong labor market, while striving for further progress in price stability. With the appropriate relaxation of policy constraints, we have good reason to believe that the economy will return to a 2% inflation rate while maintaining a strong labor market. The current level of our policy interest rate provides us with sufficient room to address any risks we may encounter, including the risk of undesired further weakening in labor market conditions.

The Rise and Fall of Inflation 通胀的起落

Let's now turn to the questions of why inflation rose, and why it has fallen so significantly even as unemployment has remained low. There is a growing body of research on these questions, and this is a good time for this discussion. It is, of course, too soon to make definitive assessments. This period will be analyzed and debated long after we are gone.

Now let's talk about why inflation rose, and why it has fallen significantly while the unemployment rate remained low. There is increasing research on these issues, and now is a good time for discussion. Of course, it is too early to make a definitive assessment. This period will be analyzed and debated long after we are gone.

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic led quickly to shutdowns in economies around the world. It was a time of radical uncertainty and severe downside risks. As so often happens in times of crisis, Americans adapted and innovated. Governments responded with extraordinary force, especially in the U.S. Congress unanimously passed the CARES Act. At the Fed, we used our powers to an unprecedented extent to stabilize the financial system and help stave off an economic depression.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic quickly led to a global economic shutdown. This was a time of great uncertainty and severe downside risks. As often happens in times of crisis, Americans adapted and innovated. Governments responded with extraordinary measures, especially the U.S. Congress unanimously passed the "CARES Act". At the Federal Reserve, we used our powers to an unprecedented extent to stabilize the financial system and help prevent an economic depression.

After a historically deep but brief recession, in mid-2020 the economy began to grow again. As the risks of a severe, extended downturn receded, and as the economy reopened, we faced the risk of replaying the painfully slow recovery that followed the Global Financial Crisis.

After experiencing a historically deep but brief recession, in mid-2020, the economy began to grow again. As the severe downward risks receded, and the economy reopened, we still faced the risk of experiencing painful slow recovery like that after the global financial crisis.

Congress delivered substantial additional fiscal support in late 2020 and again in early 2021. Spending recovered strongly in the first half of 2021. The ongoing pandemic shaped the pattern of the recovery. Lingering concerns over COVID weighed on spending on in-person services. But pent-up demand, stimulative policies, pandemic changes in work and leisure practices, and the additional savings associated with constrained services spending all contributed to a historic surge in consumer spending on goods.

The congress provided a lot of additional fiscal support at the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021. In the first half of 2021, spending recovered strongly. The ongoing pandemic affected the pattern of recovery. Concerns about the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak have weighed on in-person service spending. But pent-up demand, stimulus policies, changes in work and leisure habits due to the pandemic, and additional savings related to limited service spending have all led to a historic surge in consumer spending on goods.

The pandemic also had a severe impact on the supply side. Eight million people left the labor market at the onset of the pandemic, and the labor force was still 4 million below its pre-pandemic level in early 2021. The labor force did not return to its pre-pandemic trend until mid-2023 (figure 3). Supply chains were disrupted due to lost workers, interrupted international trade linkages, and structural changes in demand levels and composition (figure 4). Clearly, this was completely different from the slow recovery after the Global Financial Crisis.

The pandemic also severely damaged the supply side. At the start of the pandemic, 8 million people left the labor market, and the labor force was 4 million below its pre-pandemic level in early 2021. The labor force did not return to its pre-pandemic trend until mid-2023 (figure 3). Factors such as worker attrition, disrupted international trade linkages, and structural changes in demand levels and composition have put supply chains in crisis (figure 4). Clearly, this is completely different from the slow recovery after the Global Financial Crisis.

Enter inflation. After running below target through 2020, inflation spiked in March and April 2021. The initial burst of inflation was concentrated rather than broad-based, with extremely large price increases for goods in short supply, such as motor vehicles. My colleagues and I initially judged that these pandemic-related factors would not persist and, therefore, the sudden rise in inflation was likely to pass fairly quickly without the need for a monetary policy response—in short, that the inflation would be transitory. The long-standing conventional wisdom has been that as long as inflation expectations remain well anchored, it can be appropriate for central banks to overlook a temporary rise in inflation.

Inflation started to show itself. After being below the target level throughout 2020, inflation spiked in March and April 2021. The initial burst of inflation was concentrated, rather than widespread, with significant price increases for goods in short supply, such as cars. My colleagues and I initially judged that these pandemic-related factors would not persist, so the sudden rise in inflation is likely to pass quickly without the need for monetary policy measures—in short, inflation will be temporary. The conventional thinking has long been that as long as inflation expectations remain well anchored, central banks can ignore a temporary rise in inflation.

The concept of transitory inflation was widely accepted, with most mainstream analysts and central bankers in advanced economies on board. The general expectation was that supply conditions would improve relatively quickly, the rapid recovery in demand would run its course, and demand would shift back from goods to services, leading to a decrease in inflation.

"Temporary" this good ship is crowded with people, and most mainstream analysts and central bank governors of developed economies support this view. They generally expect that the supply situation will improve quickly and that the rapid recovery in demand will follow naturally, with demand shifting from goods to services, thereby reducing the inflation rate.

For a time, the data were consistent with the transitory hypothesis. Monthly readings for core inflation declined every month from April to September 2021, although progress came slower than expected (figure 5). The case began to weaken around midyear, as was reflected in our communications. Beginning in October, the data turned hard against the transitory hypothesis. Inflation rose and broadened out from goods into services. It became clear that the high inflation was not transitory, and that it would require a strong policy response if inflation expectations were to remain well anchored. We recognized that and pivoted beginning in November. Financial conditions began to tighten. After phasing out our asset purchases, we lifted off in March 2022.

For a time, the data were consistent with the transitory hypothesis. From April to September 2021, the monthly readings for core inflation declined every month, although progress was slower than expected (Figure 5). As reflected in our communications, this situation began to weaken around mid-year. Starting in October, the data diverged from the transitory hypothesis. Inflation rose and extended from goods to services. It became evident that high inflation was not temporary, and a strong policy response was needed to maintain stable inflation expectations. We recognized this and began to pivot in November. Financial conditions began to tighten. After gradually phasing out asset purchases, we began raising rates in March 2022.

By early 2022, headline inflation exceeded 6 percent, with core inflation above 5 percent. New supply shocks appeared. Russia's invasion of Ukraine led to a sharp increase in energy and commodity prices. The improvements in supply conditions and the rotation in demand from goods to services were taking much longer than expected, in part due to further COVID waves in the U.S.

By early 2022, overall inflation exceeded 6%, with core inflation exceeding 5%. New supply shocks emerged. The Russia-Ukraine conflict led to a sharp increase in energy and commodity prices. The improvement of supply conditions and the shift in demand from goods to services took much longer than expected, partially due to a new wave of COVID in the United States.

High rates of inflation were a global phenomenon, reflecting common experiences: rapid increases in the demand for goods, strained supply chains, tight labor markets, and sharp hikes in commodity prices. The global nature of inflation was unlike any period since the 1970s. Back then, high inflation became entrenched - an outcome we were fully committed to avoiding.

High inflation rates are a global phenomenon, reflecting common experiences: rapid increases in the demand for goods, strained supply chains, tight labor markets, and sharp hikes in commodity prices. The global nature of inflation is unlike any period since the 1970s. Back then, high inflation became entrenched - an outcome we were fully committed to avoiding.

By mid-2022, the labor market was extremely tight, with employment increasing by over 6-1/2 million from the middle of 2021. This increase in labor demand was met, in part, by workers rejoining the labor force as health concerns began to fade. But labor supply remained constrained, and, in the summer of 2022, labor force participation remained well below pre-pandemic levels. There were nearly twice as many job openings as unemployed persons from March 2022 through the end of the year, signaling a severe labor shortage (figure 6). Inflation peaked at 7.1 percent in June 2022.

By mid-2022, the labor market was extremely tight, with employment increasing by over 6-1/2 million from the middle of 2021. This increase in labor demand was met, in part, by workers rejoining the labor force as health concerns began to fade. But labor supply remained constrained, and, in the summer of 2022, labor force participation remained well below pre-pandemic levels. There were nearly twice as many job openings as unemployed persons from March 2022 through the end of the year, signaling a severe labor shortage (figure 6). Inflation peaked at 7.1 percent in June 2022.

At this podium two years ago, I discussed the possibility that addressing inflation could bring some pain in the form of higher unemployment and slower growth. Some argued that getting inflation under control would require a recession and a lengthy period of high unemployment. I expressed our unconditional commitment to fully restoring price stability and to keeping at it until the job is done.

At this podium two years ago, I discussed the possibility that addressing inflation could bring some pain in the form of higher unemployment and slower growth. Some argued that getting inflation under control would require a recession and a lengthy period of high unemployment. I expressed our unconditional commitment to fully restoring price stability and to keeping at it until the job is done.

The FOMC did not flinch from carrying out our responsibilities, and our actions forcefully demonstrated our commitment to restoring price stability. We raised our policy rate by 425 basis points in 2022 and another 100 basis points in 2023. We have held our policy rate at its current restrictive level since July 2023 (figure 7).

The FOMC did not flinch from carrying out our responsibilities, and our actions forcefully demonstrated our commitment to restoring price stability. We raised our policy rate by 425 basis points in 2022 and another 100 basis points in 2023. We have held our policy rate at its current restrictive level since July 2023 (figure 7).

The summer of 2022 proved to be the peak of inflation. The 4-1/2 percentage point decline in inflation from its peak two years ago has occurred in a context of low unemployment—a welcome and historically unusual result.

Inflation reached its peak in the summer of 2022. The 4.5% decline in inflation from its peak two years ago is a welcome and historically unusual result in the context of low unemployment.

How did inflation fall without a sharp rise in unemployment above its estimated natural rate?

How did inflation fall without a sharp rise in unemployment above its estimated natural rate?

Pandemic-related distortions to supply and demand, as well as severe shocks to energy and commodity markets, were important drivers of high inflation, and their reversal has been a key part of the story of its decline. The unwinding of these factors took much longer than expected but ultimately played a large role in the subsequent disinflation. Our restrictive monetary policy contributed to a moderation in aggregate demand, which combined with improvements in aggregate supply to reduce inflationary pressures while allowing growth to continue at a healthy pace. As labor demand also moderated, the historically high level of vacancies relative to unemployment has normalized primarily through a decline in vacancies, without sizable and disruptive layoffs, bringing the labor market to a state where it is no longer a source of inflationary pressures.

Pandemic-related distortions to supply and demand, as well as severe shocks to energy and commodity markets, were important drivers of high inflation, and their reversal has been a key part of the story of its decline. The unwinding of these factors took much longer than expected but ultimately played a large role in the subsequent disinflation. Our restrictive monetary policy contributed to a moderation in aggregate demand, which combined with improvements in aggregate supply to reduce inflationary pressures while allowing growth to continue at a healthy pace. As labor demand also moderated, the historically high level of vacancies relative to unemployment has normalized primarily through a decline in vacancies, without sizable and disruptive layoffs, bringing the labor market to a state where it is no longer a source of inflationary pressures.

A word on the critical importance of inflation expectations. Standard economic models have long reflected the view that inflation will return to its objective when product and labor markets are balanced—without the need for economic slack—so long as inflation expectations are anchored at our objective. That's what the models said, but the stability of longer-run inflation expectations since the 2000s had not been tested by a persistent burst of high inflation. It was far from assured that the inflation anchor would hold. Concerns over de-anchoring contributed to the view that disinflation would require slack in the economy and specifically in the labor market. An important takeaway from recent experience is that anchored inflation expectations, reinforced by vigorous central bank actions, can facilitate disinflation without the need for slack.

The importance of inflation expectations. Over the long term, standard economic models have always reflected the view that as long as inflation expectations are anchored to our target, when the product and labor markets reach equilibrium, inflation will return to its target without causing economic slack. That's what the model says, but since the 2000s, the stability of long-term inflation expectations has not been tested by sustained high inflation. It is far from guaranteed whether inflation can continue to be anchored. Concerns about being unanchored have led to a view that disinflation will require economic (especially labor market) slackening. An important conclusion drawn from recent experiences is that anchored inflation expectations, coupled with strong central bank actions, can facilitate disinflation without the necessity of economic slackening.

This narrative attributes much of the increase in inflation to an extraordinary collision between overheated and temporarily distorted demand and constrained supply. While researchers differ in their approaches and, to some extent, in their conclusions, a consensus seems to be emerging, which I see as attributing most of the rise in inflation to this collision. All told, the healing from pandemic distortions, our efforts to moderate aggregate demand, and the anchoring of expectations have worked together to put inflation on what increasingly appears to be a sustainable path to our 2 percent objective.

This narrative attributes much of the increase in inflation to an extraordinary collision between overheated and temporarily distorted demand and constrained supply. While researchers differ in their approaches and, to some extent, in their conclusions, a consensus seems to be emerging, which I see as attributing most of the rise in inflation to this collision. All told, the healing from pandemic distortions, our efforts to moderate aggregate demand, and the anchoring of expectations have worked together to put inflation on what increasingly appears to be a sustainable path to our 2 percent objective.

Disinflation while preserving labor market strength is only possible with anchored inflation expectations, which reflect the public's confidence that the central bank will bring about 2 percent inflation over time. That confidence has been built over decades and reinforced by our actions.

Disinflation while preserving labor market strength is only possible with anchored inflation expectations, which reflect the public's confidence that the central bank will gradually achieve the inflation target of around 2%. This confidence has been built up over the past few decades and strengthened by our actions.

That is my assessment of events. Your mileage may vary.

This is my assessment of events. Your mileage may vary.

Conclusion

Let me wrap up by emphasizing that the pandemic economy has proved to be unlike any other, and that there remains much to be learned from this extraordinary period. Our Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy emphasizes our commitment to reviewing our principles and making appropriate adjustments through a thorough public review every five years. As we begin this process later this year, we will be open to criticism and new ideas, while preserving the strengths of our framework. The limits of our knowledge—so clearly evident during the pandemic—demand humility and a questioning spirit focused on learning lessons from the past and applying them flexibly to our current challenges.

Finally, I would like to emphasize that the pandemic economy is unlike any other, and there is still much for us to learn from this unique period. Our Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy emphasizes our commitment to reviewing our principles and making appropriate adjustments through a comprehensive public review every five years. As we start this process later this year, we will be open to criticism and new ideas, while preserving the strengths of our framework. The limitations of our knowledge - as clearly evident during the pandemic - require us to be humble and inquisitive, focusing on learning lessons from the past and applying them flexibly to our current challenges.

Note: The original text of Chairman Powell's speech can be found on the official website of the Federal Reserve, and the Wall Street Journal has made some edits.

他认为,目前的政策利率水平为美联储提供了充足的空间来应对可能面临的任何风险,包括劳动力市场状况进一步恶化的风险。“通胀的上行风险已经减弱,就业的下行风险则有所增加。美联储关注双重使命各自所面临的风险。”

他认为,目前的政策利率水平为美联储提供了充足的空间来应对可能面临的任何风险,包括劳动力市场状况进一步恶化的风险。“通胀的上行风险已经减弱,就业的下行风险则有所增加。美联储关注双重使命各自所面临的风险。”