Max recently released a memorandum titled "Revisiting the Bubble," stating that investors are currently betting on the leading high-tech companies to maintain their dominance. However, he believes that it is not easy to stay ahead, as new technologies and competitors can surpass existing market leaders at any time. When people assume that "things can only get better" and Buy based on that, the impact of negative news can be particularly severe. He specifically pointed out the frenzy over AI and how this positive sentiment may spread to other Technology sectors.

Howard Marks, the founder of Oaktree Capital, recently published his first memo of 2025 titled "On-Bubble-Watch," discussing the most concerning issue for investors in the USA stock market: is there a bubble in the stock market, especially with the Magnificent 7?

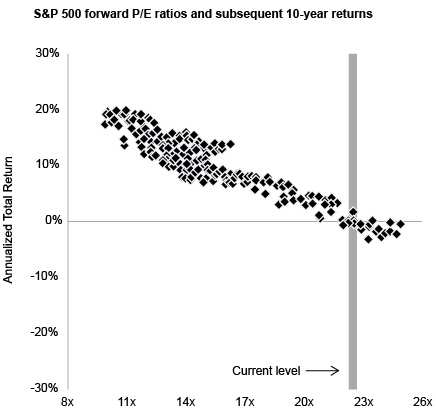

Marks pointed out that new things are prone to create bubbles. Currently, investors are betting that the leading high-tech companies will maintain their lead; however, he believes it is not easy to sustain this lead, as new technologies and competitors could surpass the current market leaders at any moment. When people assume that "things will only get better" and buy accordingly, the impact of negative news will be particularly severe. If one buys the S&P 500 at the current PE ratio, historical data shows that one can only achieve a 10-year return of between -2% to 2%. He specifically highlighted the frenzy around new technologies like AI and how this positive sentiment could spill over into other high-tech sectors.

Wall Street Insight has summarized the core points of Marks' memo:

Wall Street Insight has summarized the core points of Marks' memo:

1. Bubbles or crashes are more like a psychological state rather than a quantitative calculation. When everyone believes that the future will only get better, it becomes difficult to find reasonably priced assets.

2. Bubbles are always closely linked to emerging things. Because if something is completely new, it implies that there is no historical reference, and thus nothing can suppress the market's frenzy.

3. When something is elevated to a popular pedestal, the risk of it declining becomes very high. When people assume that "things will only get better" and buy accordingly, the impact of negative news can be particularly severe. The optimism surrounding new things often magnifies mistakes, leading to their stocks being assigned inflated valuations.

4. The leading companies in the current S&P 500 Index are, in many ways, much better than the best companies of the past. They possess strong technological advantages, vast scale, and dominant market share, resulting in profit margins that are far above average. The PE ratio is not exaggerated like it was during the "Nifty Fifty" era of the 1960s.

Currently, investors are betting on leading high-tech companies that can maintain their advantage. However, in the high-tech field, it is not easy to stay ahead because new technologies and competitors can overtakes existing market leaders at any time. It is important to remember that even the best companies can lose their leading position and face significant risks when prices are too high.

The most dangerous thing in the world is to "think there is no risk." Similarly, since people have observed that stocks have never performed poorly in the long term, they enthusiastically buy stocks, pushing prices to levels that are inevitably going to perform poorly. If stock prices rise too quickly, far exceeding the company's profit growth rate, it is unlikely to sustain that rise.

Buying the S&P 500 at the current PE indicates that historical data shows only a potential return of -2% to 2% over ten years. If stock prices remain unchanged over the next decade and company profits continue to grow, the PE will gradually return to normal levels. However, another possibility is that the valuation adjustment occurs within one or two years, leading to significant declines similar to those of 1973-1974 or 2000-2002. The outcome in such situations is less favorable.

Max also listed several warning signs in the market, including general optimism in market sentiment since the end of 2022; S&P 500 Index valuations are above average, and most industry stocks have PEs higher than similar stocks in other parts of the world; enthusiasm for new technologies such as AI, and this positive sentiment may spread to other high-tech sectors; the implicit assumption about the continuous success of the "Seven Sisters" companies; and index funds automatically buying these stocks that may push stock prices up while ignoring their intrinsic value.

Here are the key points organized by Wall Street Insight:

In the first decade of this century, investors experienced two remarkable bubbles—resulting in significant losses.

The first was the Internet bubble at the end of the 90s, which began to burst in mid-2000; the second was the housing bubble in the mid-2000s, which led to the following consequences: (a) granting mortgages to subprime borrowers who could not or were unwilling to prove income or assets; (b) structuring these loans into leveraged, tiered mortgage-backed securities; (c) ultimately leading to significant losses for investors, especially financial institutions that created and held portions of these securities.

Due to these experiences, many people are currently highly vigilant about bubbles, and I am often asked whether there is a bubble phenomenon in the S&P 500 Index and its dominant stocks.

The seven stocks with the highest Market Cap in the S&P 500 Index, known as the 'Magnificent Seven,' are Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet (the parent company of Google), Amazon, NVIDIA, Meta (the parent company of Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram), and Tesla. In short, a handful of stocks have dominated the S&P 500 Index in recent years, contributing disproportionately to the increase.

A chart from Michael Cembalest, Chief Strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, shows:

- As of the end of October, the seven largest companies in the S&P 500 Index accounted for 32% to 33% of the total Market Cap of the index;

- This proportion is about twice that of the leading companies five years ago;

- Before the rise of the 'Magnificent Seven,' the highest recorded proportion for the top seven stocks over the past 28 years was around 22% during the peak of the 2000 TMT bubble.

Another important piece of data shows that as of the end of November, US Stocks accounted for over 70% of the MSCI Global Index, the highest percentage since 1970, which also comes from Cembalest's chart. Therefore, it is clear that: first, the Market Cap of US companies is very high compared to those in other regions; second, the value of the seven companies with the highest Market Cap in the USA is even more prominent in comparison to other US stocks.

But, does this count as a bubble?

A bubble is more of a psychological state.

In my opinion, a bubble or crash is more of a psychological state rather than a quantitative calculation. A bubble not only reflects the rapid rise in stock prices but also manifests as a temporary frenzy characterized by—or more precisely, caused by the following factors:

1. Extremely irrational optimistic sentiment (borrowing the term 'irrational exuberance' from former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan);

2. Extreme idolization of the relevant companies or assets, along with the belief that they cannot fail;

3. Fear of missing out (FOMO), worrying that not participating will leave one behind;

4. The resulting belief that for these stocks, 'no price is too high.'

To identify a bubble, one can look at valuation indicators, but I have long believed that psychological analysis is more effective. Whenever I hear 'no price is too high' or similar statements—even if more cautious investors say, 'Of course, prices can be too high, but we haven't reached that point yet'—I take it as a clear signal that a bubble is brewing.

About fifty years ago, a predecessor gave me one of my favorite maxims. I have written about it in several memos, but I think it is worth emphasizing again. It is 'the three phases of a bull market':

1. The first phase typically occurs after a market decline or crash, during which most investors are disheartened and bruised, and only a few sharp-eyed individuals can envision a potential recovery in the future.

2. Phase two, the economy, companies, and market perform well, and most people begin to accept that the situation is indeed improving.

3. Phase three, as economic news continues to be bullish, company reports show substantial profit increases, and stock prices soar, everyone believes that the future will only get better.

What matters is not the actual performance of the economy or businesses, but the psychology of investors. This is not about what is happening in the macro world, but how people perceive these developments. When few believe that the situation will improve, stock prices clearly do not reflect much optimism. But when everyone believes that the future will only get better, it becomes difficult to find reasonably priced assets.

New things stimulate the generation of bubbles.

Bubbles are always closely linked to new phenomena. In the 1960s, the bubble of the "Nifty Fifty" stocks in the USA, the bubble of disk drive companies in the 1980s, the Internet bubble at the end of the 1990s, and the bubble of subprime mortgage-backed securities from 2004 to 2006 all followed similar trajectories.

Under normal circumstances, if the securities of a particular industry or country attract unusually high valuations, investment historians often point out: in the past, the valuation premium of these stocks has never exceeded a certain percentage of the average level or provide other similar indicators. The historical reference acts like a leash, keeping the sought-after group of stocks anchored to reality, preventing them from flying too far.

But if something is entirely new, meaning there is no history to refer to, then there is nothing to restrain the market's frenzy. After all, these stocks are owned by the smartest people—those star investors who frequently appear in headlines and on television, and who have made a fortune. Who would want to pour cold water on such a festive party, or refuse to join this dance?

Like in "The Emperor's New Clothes," the con artist sells the emperor a set of splendid clothes that supposedly only smart people can see, but in reality, there are no clothes at all. As the emperor parades naked through the town, the citizens are afraid to admit that they see no clothing, for that would make them seem not smart enough.

In the investment market, most people prefer to go with the flow, accepting the collective fantasy that can swiftly make investors wealthy, rather than standing up to voice opposing opinions, risking being viewed as "fools." When the entire market or a certain class of securities is soaring, and an untenable notion allows believers to accumulate wealth, few dare to risk exposing the truth.

Buying the "Nifty Fifty" resulted in a 90% loss.

I joined the stock research department of First National City Bank (now Citigroup) in September 1969. Like most so-called "money center banks," Citigroup primarily invested in the "Nifty Fifty," stocks considered to be the best and fastest-growing companies in the USA. These companies were perceived as too good to encounter problems, and their stocks were believed to have no "overvalued" prices.

Investor obsession with these stocks stemmed from three factors. First, the USA experienced robust economic growth after World War II. Second, these companies were involved in innovative fields such as computers, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods. Third, they represented the first wave of "growth stocks," a new style that later became fashionable in investing.

Thus, the "Nifty Fifty" became the first major bubble component in 40 years. Having not experienced a bubble for a long time, investors had already forgotten what a bubble looked like. Consequently, on the day I started working, purchasing these stocks and holding them for five years resulted in losing over 90% of funds in these top American companies. What exactly happened?

"Nifty Fifty" was idolized, and when something falls from its pedestal, investors get hurt. Between 1973-74, the entire stock market declined by about half. It turned out that the prices of these stocks were indeed outrageous; in many cases, their PE ratio fell from a range of 60-90 times to 6-9 times (this is the simple calculation of losing 90% of Assets). Additionally, from a fundamental perspective, several of these companies did encounter genuine bad news.

A genuine bubble I experienced early on allowed me to summarize some guiding principles that benefited me greatly over the next 50 years:

1. The key is not what you bought, but how much you paid.

2. Excellent investment does not come from buying good assets, but rather from buying assets at good prices.

3. No asset is so good that it cannot be overvalued and become dangerous, and no asset is so bad that it cannot become cheap enough to become a worthwhile trade.

The higher it is held, the heavier it falls.

The bubbles I have experienced all involve innovation, many of which, as previously mentioned, are either overvalued or not fully understood. The appeal of new products or business models is often obvious, but the traps and risks are often hidden, only to be revealed during difficult times.

A new company may completely surpass its predecessors, but inexperienced investors often overlook the fact that even the most dazzling new star can be replaced. Disruptors themselves can also be disrupted, either by more skilled competitors or by newer technologies.

In my early business career, technology seemed to develop gradually. But by the 1990s, innovation suddenly accelerated. Oak Tree Capital was founded in 1995, when investors firmly believed that "the Internet would change the world." This viewpoint seemed very reasonable and led to a tremendous demand for everything related to the Internet in the market. E-commerce companies went public at seemingly high prices, and their stock prices tripled on the first day, sparking a true gold rush.

When something is elevated to the platform of popularity, the risk of its decline becomes very high. When people assume that "things will only get better" and buy accordingly, the impact of negative news can be particularly severe. The optimism surrounding new things often further amplifies errors, leading to their stock prices being assigned excessive valuations.

1. As mentioned earlier, there is a lack of Historical Data to gauge a reasonable valuation for new things.

2. Moreover, the potential of these companies has not yet translated into stable profits, which means the valuation is essentially guesswork. During the Internet bubble, these companies were not profitable, making the PE Index irrelevant. As startups, they often do not even have revenue, forcing investors to invent new metrics – such as 'clicks' or 'eyeballs' – the ability of which to convert into revenue and profit is completely unknown.

3. Because bubble participants cannot imagine any potential risks, they tend to assign valuations assuming success.

4. In reality, investors even tend to view all competitors in new fields as potentially successful, while in practice only a few companies can truly survive or succeed.

Ultimately, in the realm of hot new things, investors often adopt what I refer to as a 'lottery mentality.' If a successful startup in a hot area can yield a 200-fold return, even with just a 1% probability of success, from a mathematical perspective, it is worth investing. So, what scenario does not have at least a 1% chance of success? When investors think this way, they almost never limit their investments or the prices they are willing to pay.

Clearly, investors can easily become caught up in the race to buy the latest hot items, which is precisely why bubbles form.

How much is a fair price to pay for a bright future? It is rare to be ahead.

If there is a company expected to earn 1 million dollars next year and then shut down, how much would you be willing to pay to buy it? The correct answer is slightly less than 1 million dollars, so you can achieve a positive return.

But stocks are often priced based on the 'PE ratio', which is a multiple of the company's expected profit next year. Why? Because people assume that a company won’t just be profitable for one year but will continue to earn for many years. When you buy a stock, you are essentially purchasing a share of the company's profits for each year in the future.

In reality, the current value of the company is the present value of its future earnings discounted at a certain rate. Therefore, a PE of 16 actually implies that you are paying for more than 20 years of earnings (depending on the rate at which future earnings are discounted).

During the bubble period, the trading prices of popular stocks were far above 16 times earnings. For example, the PE ratio of "Nifty Fifty" stocks once reached as high as 60 to 90 times! Investors in 1969, when paying these high prices, even considered profit growth for decades into the future. So, were they consciously and analytically deriving this valuation? I don't recall such a situation. At that time, investors simply viewed the PE ratio as just another number.

So, are today's market leaders any different? The leading companies in the current S&P 500 Index are far superior in many aspects compared to the best companies of the past. They possess strong technological advantages, massive scale, and dominant market shares, leading to profit margins well above average. Moreover, as these companies rely more on "creativity" rather than physical products, the marginal cost of producing additional units is lower, implying exceptionally high marginal profitability.

More notably, the PE ratios of today's market leaders are not as exaggerated as during the "Nifty Fifty" era. For example, NVIDIA, regarded as the "hottest" company as a leading designer of AI chips, has a PE ratio of about 30 times. Though this PE ratio is twice the post-war average PE of the S&P 500 Index, it still appears cheap compared to the "Nifty Fifty."

However, what does a PE of over 30 actually mean? First, investors believe that NVIDIA will continue to operate for decades to come; second, investors trust that its profits will continue to grow in the coming decades; third, they assume NVIDIA will not be replaced by competitors. In other words, investors are betting on NVIDIA being able to maintain its continuous leading position.

However, sustaining a leading position in the high-tech field is not easy, as new technologies and competitors could potentially outpace existing market leaders at any time. For instance, according to the "Nifty Fifty" list listed by Wikipedia, only about half of those companies are still in the S&P 500 Index today.

Once star companies, such as Xerox, Eastman Kodak, Polaroid, Avon, Burroughs, Digital Equipment, and Simplicity Pattern, are no longer part of the S&P 500 Index.

According to finhacker.cz, at the beginning of 2000, the 20 largest companies by market cap in the S&P 500 Index were:

1. Microsoft (Microsoft)

2. Merck (Merck)

3. General Electric (General Electric)

4. Coca-Cola (Coca-Cola)

5. Cisco Systems (Cisco Systems)

6. Procter & Gamble (Procter & Gamble)

7. Walmart (Walmart)

8. American International Group (AIG)

9. Exxon Mobil (Exxon Mobil)

10. Johnson & Johnson (Johnson & Johnson)

11. Intel (Intel)

12. Qualcomm (Qualcomm)

13. Citigroup (Citigroup)

14. Bristol-Myers Squibb (Bristol-Myers Squibb)

15. IBM (IBM)

16. Pfizer (Pfizer)

17. Oracle

18. AT&T

19. Home Depot

20. Verizon

However, by early 2024, only 6 of these companies remain in the top 20:

1. Microsoft

2. Johnson & Johnson

3. Walmart

4. Procter & Gamble

5. Exxon Mobil

6. Home Depot

More importantly, among today's "Magnificent Seven," only Microsoft broke into the top 20 ranks 24 years ago.

Therefore, during the bubble period, investors had extremely high expectations for leading companies and were willing to pay a premium for their stocks, as if these companies were destined to continue leading for decades to come. However, the reality is often that change is more common than continuity. Investors need to remember that even the best companies can lose their leading position and face enormous risks when prices are too high.

Believing that there is no risk is the most dangerous.

The most severe bubbles often originate from innovation, mainly in the realms of technology or finance, initially affecting only a small number of stocks. However, sometimes this bubble can expand across the entire market, as the enthusiasm for a certain bubble sector spreads to all areas.

For example, in the 1990s, the S&P 500 Index continued to rise due to two major factors: first, the sustained decline in interest rates that peaked in the early 1980s to combat inflation; and second, the renewed enthusiasm for stocks among investors, which had faded after the trauma of the 1970s. The technological innovations and rapid profit growth of high-tech companies further fueled this enthusiasm.

Meanwhile, new academic research indicates that there has never been a time in history when the S&P 500 performed worse than Bonds, Cash, or inflation over the long term. These positive factors combined resulted in an average annual return of over 20% for the index in the 1990s. Such a period has never been seen before.

I often say that the most dangerous thing in the world is to "believe there is no risk." Similarly, because people observe that Stocks have never performed poorly in the long term, they fervently buy Stocks, leading to prices being pushed to levels that will inevitably perform poorly. In my view, this reflects the investment "reflexivity" theory proposed by George Soros.

After the Internet bubble burst, the S&P 500 Index fell for three consecutive years in 2000, 2001, and 2002, the first time this had occurred since the Great Depression of 1939. Due to poor market performance, investors massively sold off Stocks, leading the S&P 500 Index to have an accumulated return of zero from the 2000 bubble high point to December 2011, lasting over 11 years.

Recently, I often quote a saying, which I believe is from Warren Buffett: "When investors forget that a company's profit grows at an average rate of about 7% per year, they often get into trouble." This means that if a company’s profit grows by 7% each year, but the stock price rises by 20% each year in the short term, eventually the stock price will be so high that it is fraught with risk.

The key point is that if stock prices rise too rapidly, far exceeding the company’s profit growth rate, it is unlikely to sustain that growth.

A chart provided by Michael Sanbarrest illustrates this well. The data shows that two years ago, the S&P 500 Index had only four occurrences of rising consecutively over 20% for two years. In three of these four instances, it fell in the subsequent two years. (The only exception was from 1995 to 1998, where the technology bubble strongly propelled growth, with declines delayed until 2000, but subsequently the index fell nearly 40% over three years).

And in the past two years, this has occurred for the fifth time. The S&P 500 Index rose by 26% in 2023 and 25% in 2024, marking the best two-year performance since 1997-1998. So what will happen in 2025?

Current market warning signals.

Here are a few signs that need to be cautious about:

- Since the end of 2022, the market has generally been optimistic;

- The valuation of the S&P 500 Index is above average, and most industry stocks have PE ratios higher than their peers in other parts of the Global.

- The frenzy over new technologies, such as AI, and this positive sentiment may spread to other high-tech areas.

- The implicit assumption of the continued success of the 'Magnificent Seven' companies.

- Index funds automatically buy these stocks, which may drive up stock prices while ignoring their intrinsic value.

In addition, despite being unrelated to the stock market, I must mention Bitcoin. Regardless of whether its value is reasonable, it has increased by 465% over the past two years, which does not indicate an excessively cautious sentiment in the market.

On the eve of releasing this memo, I received a chart from JPMorgan's Asset Management department. This chart shows monthly data from 1988 to 2014 (a total of 324 months) reflecting the relationship between the S&P 500's PE ratio and the annualized returns over the following decade.

The following points are worth noting:

1. There is a significant correlation between initial valuation and subsequent 10-year annualized returns: the higher the starting valuation, the lower the subsequent returns, and vice versa.

2. The current PE is clearly at the high end of the historical data, in the top 10%.

3. During this 27-year period, when the S&P 500's PE was around the current level of about 22 times, the subsequent 10-year returns ranged between +2% and -2%.

Some banks have recently projected that the S&P 500's returns over the next decade will be in the middle to low single digits. Therefore, investors should clearly not overlook the current market valuation.

Of course, one might say, "A return of ±2% over the next decade isn't too bad." Indeed, if stock prices remain unchanged over the next decade while company profits continue to grow, it will gradually restore the PE to normal levels. But another possibility is that the valuation adjustment could be compressed to happen within one or two years, leading to significant declines similar to those seen in 1973-1974 or 2000-2002. The results in this scenario would not be as friendly.

Of course, there are also some counterarguments to the view that the current market is overvalued, including:

- Although the PE of the S&P 500 is high, it is not yet considered crazy;

- The "Seven Sisters" are extremely powerful companies, so their high PE may be justifiable;

- I have not heard anyone say "the price is not high enough";

- Although the market is priced high and may even have some bubble, it is overall quite rational.

I am not a stock investor nor a technical expert. Therefore, I cannot authoritatively determine whether we are in a bubble. I am simply listing the facts I see and suggesting how to think about these issues.

华尔街见闻整理了此次马克斯备忘录的核心观点:

华尔街见闻整理了此次马克斯备忘录的核心观点: